“Dual Narratives”

You are not the center of the universe.

Of all the hard lessons we learn growing up, this may be the hardest. Discovering that the world won’t always give us what we want, when we want it, is hard. Understanding that other people see things differently from us and, what’s more, they may be right, is really hard.

As with so many things (maybe everything?), books can help. By their very nature, stories ask us to see through other eyes. Reading, we live inside other heads, share the joys, sorrows and fears of other hearts. Whenever I visit schools, I ask kids for book recommendations. I’ll never forget the look on a fourth grader’s face as she raptly described a book where two characters experienced the exact same thing but described it in two totally different ways. Hers was the look of revelation!

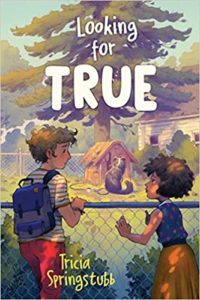

Before Looking for True, I’d never succeeded in writing a boy main character. Somehow I could never find the right voice–I’m not sure why. Maybe I was waiting for Jude, a guy who’s actually pretty stingy with his words but nonetheless started whispering in my ear. Quiet as he is, I needed to introduce Jude to Gladys, who is a blabbermouth. Then along came True, an abused dog. While Jude labels her ugly and Gladys calls her adorable, each of them feels the pullind a connect with True

Writing from two points of view, I could show how Gladys knows Jude is in love with True long before Jude does. I could show how Jude, who’s got lots of trouble at home, thinks Gladys has a perfect family, even as Gladys, who’s adopted, worries about losing her parents’ love. Meanwhile, the god-like reader gets to see not only how often they misunderstand each other but also how, by caring for True, they slowly discover all they share. For me, someone who usually writes a close third point of view, this was as close to omniscience as I’ll ever get. I loved writing this book.

A dual narrative can be great fun for students to try. They can do this in a quick writing prompt, describing something (a blizzard, a rock concert) from two points of view (a school kid, a tired parent). In stories, a dual narrative gives them the freedom to write shorter scenes and try out different voices. While some students will choose to create a clear antagonist and protagonist, others will find themselves puzzling over how the characters are different, where they connect, and what it all might mean.

Some wonderful mentor texts, stories told from two (or sometimes more) point of view:

- So Done by Paula Chase is a powerful YA about two girls whose long friendship is fraying after a summer apart. Chase explores ambition, secrets, and loyalty.

- Pax by Sarah Pennypacker is a remarkable MG novel about a boy and the fox he has raised from a kit, told from both the child’s and the animal’s points of view.

- We Dream of Space by Erin Entrada Kelly gives voice to three siblings, each tracing a separate orbit in a troubled family. This historical MG is about science, resilience and the enduring bonds brothers and sisters share.

- Alfie (The Turtle That Disappeared) by Thyra Heder is a whimsical picture book where, halfway through, the perspective switches from the child to Alfie. Only the reader gets to know the full story!

You are not the center of the universe. A hard lesson! But writing and reading stories with multiple narrators teaches us this: You are one shining light in a wide, wonderful galaxy of fellow stars.

Published November 1st, 2022 by Margaret Ferguson Books

About the Book: Though they live in the same small, Rust Belt town, there’s no way Jude and Gladys—a quiet, sullen boy big for his age and a tiny, know-it-all girl– could ever be friends.

Until…along comes a dog with a crooked tail and true-blue eyes. Gladys has never liked dogs, and Jude’s afraid of them, but this one, who’s being sadly mistreated, tugs at both their hearts. They hatch a plan to hide True in an abandoned house on the edge of town till they can figure out a better solution. As their ties to the dog–and to one another–deepen, the idea of giving her up becomes impossible. Keeping such a big secret becomes increasingly difficult. Then True’s owner offers a big return for her return–money Jude’s family desperately needs. The friendship, and True’s fate, hangs in the balance.

Told in alternating voices, this fresh, moving, suspenseful novel explores the joys and challenges of opening our hearts to others, whether they have two legs or four.

“A heartfelt contemporary novel about unexpected friendship that kicks off with a Because of Winn-Dixie–tinged bond. . . . Springstubb gracefully conveys their need for both connection and independence, portraying sweet, protective relationships that each has with young children. Alternating third-person perspectives render unique characterizations.”—Publishers Weekly

“A bighearted novel. . . .”—Kirkus Reviews

About the Author: Tricia is the author of many books for children, including the award winning middle grade novels What Happened on Fox Street, Moonpenny Island and Every Single Second. She’s also written four books in the Cody chapter book series, illustrated by Eliza Wheeler, as well as the picture book Phoebe and Digger, illustrated by Jeff Newman. Her newest picture book, Khalil and Mr. Hagerty and the Backyard Treasures, illustrated by Elaheh Taherian, is an ALA Notable Book. Kirkus called her 2021 middle grade The Most Perfect Thing in the Universe, a “perfect thing in the universe of juvenile literature.” Her next novel, Looking for True, publishes November 1, 2022. Tricia has worked as a Head Start teacher and a children’s library associate. Besides writing and, of course, reading, she loves doing school and library visits. Mother of three grown daughters and four perfect grandbabies, she lives with her husband, garden and cats in Cleveland Heights, Ohio. You can follow her on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram, and contact her at www.triciaspringstubb.com

Thank you, Tricia, for this reflection and recommendations!