“Teaching Activities Related to James Baldwin’s Extraordinary Life”

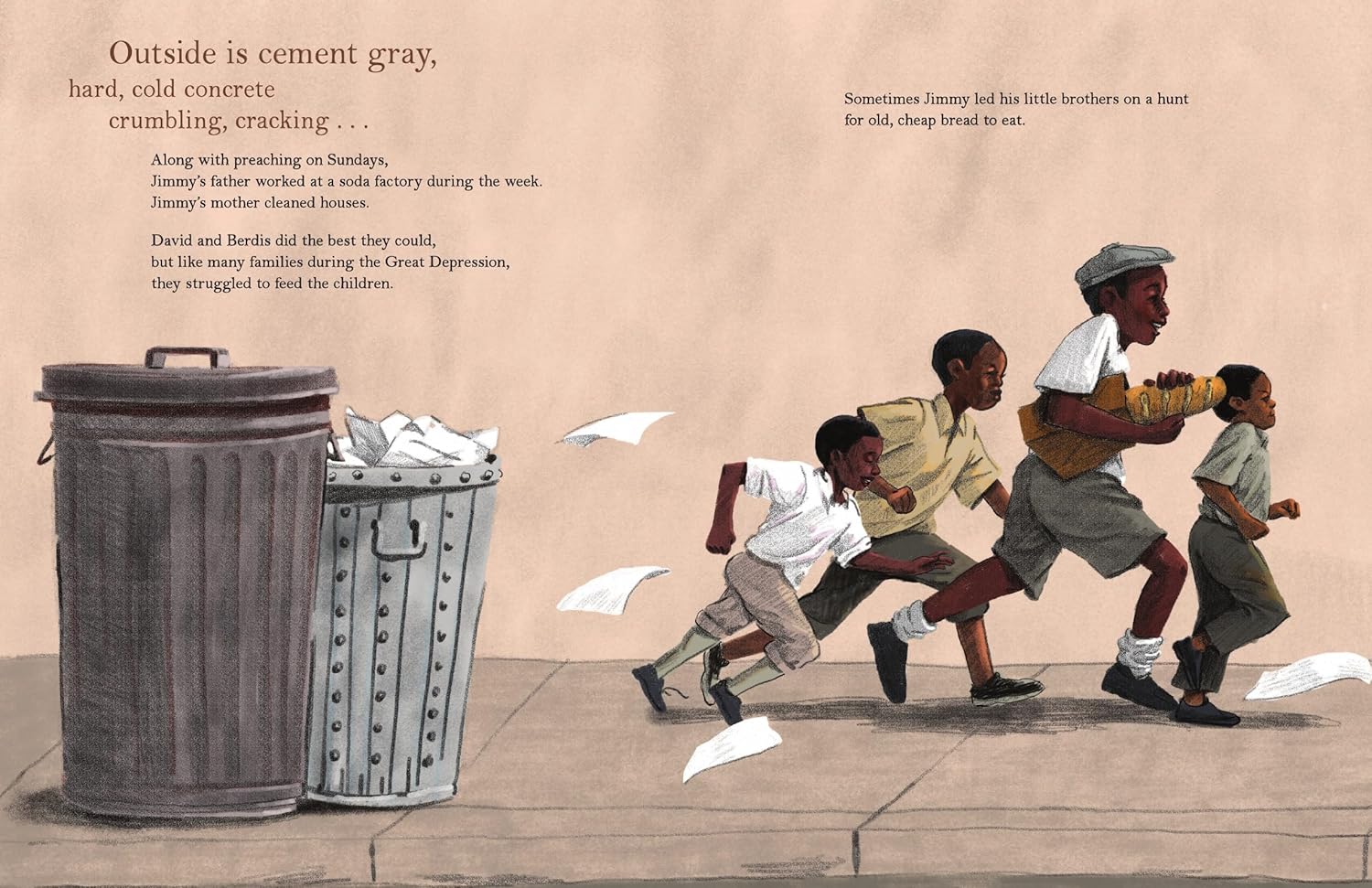

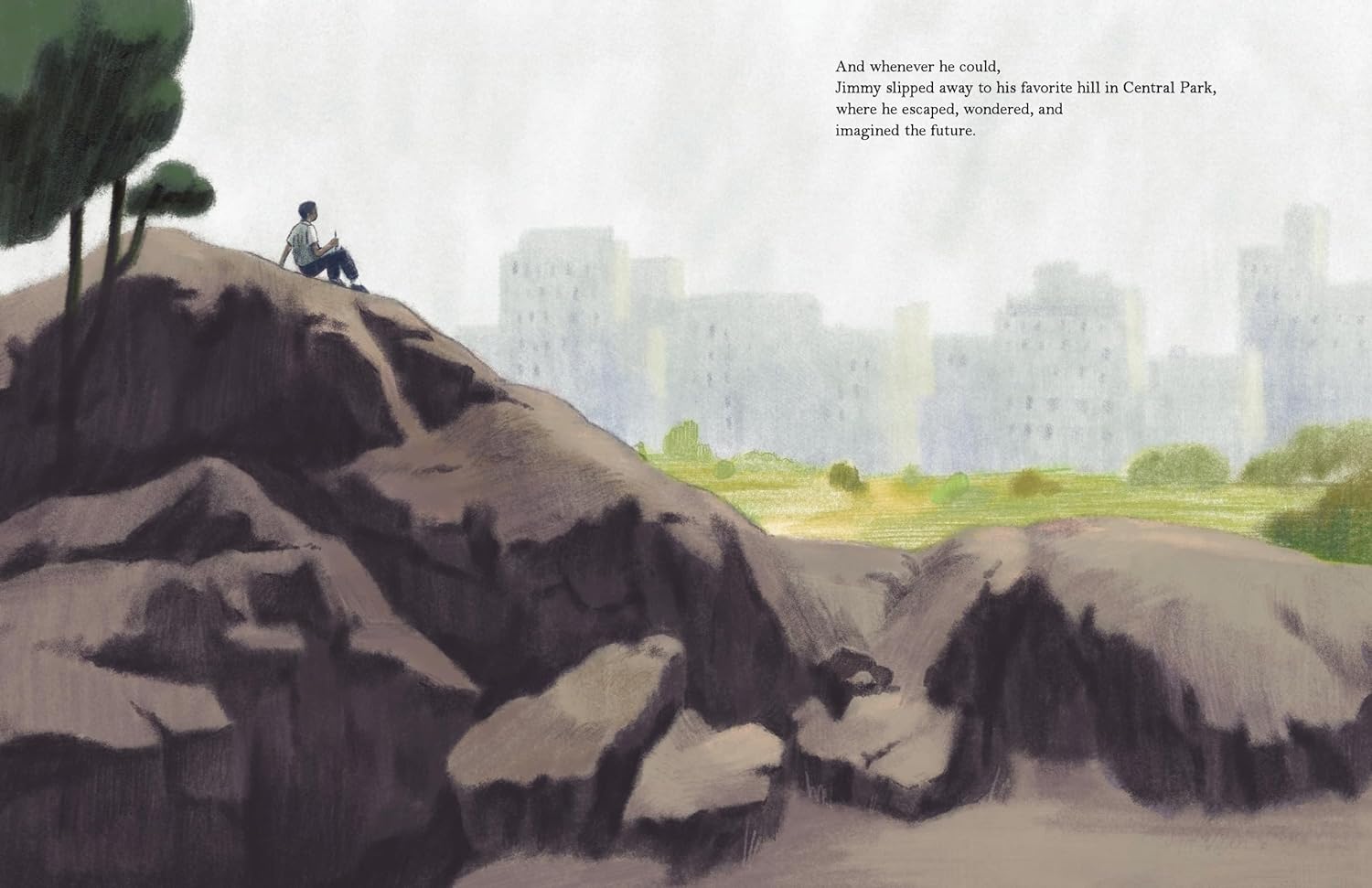

James Baldwin wrote more than 20 works of fiction and nonfiction, including essays, plays, short stories, poems, and novels. Before he became a legendary writer and civil rights activist, he was a young boy from Harlem who loved books and the library. His friends and family called him Jimmy.

Here are five ways to inspire students to learn from James Baldwin’s phenomenal life and boost their self-awareness at the same time. These activities can be used as discussion points or writing exercises.

Set Goals

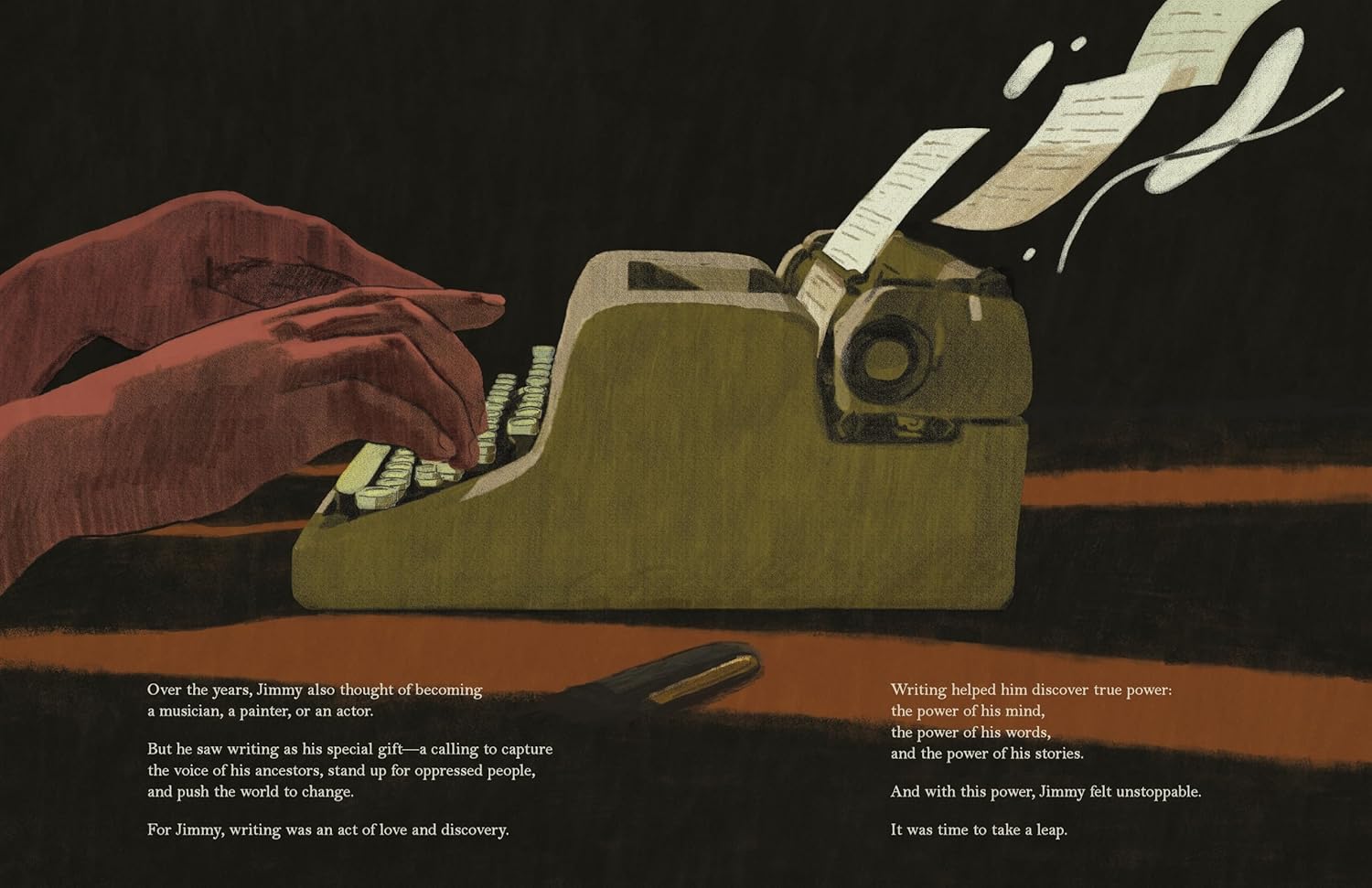

From a young age, Jimmy knew he wanted to be a writer. He devoured books, loved the rhythm of words, and felt that writing soothed him. One day, he shared his deepest dream with his mother: “I’m going to be a great writer when I grow up.”

Activity # 1: After reading the book JIMMY’S RHYTHM & BLUES: The Extraordinary Life of James Baldwin, students will enjoy picking out various moments that show Baldwin’s interest in writing. Explain to kids that they don’t have to know all their goals now, but that it’s wonderful to set goals related to activities you enjoy. Invite students to address: What are your goals right now? What are you doing to achieve them?

Celebrate Supporters

Jimmy’s teachers noticed he had a gift for weaving words together like musical notes of a song. This book highlights his most significant supporters, including a theater teacher named Orilla Winfield. Her nickname was Bill. Bill encouraged Jimmy’s interest in the arts by taking him to museums, movies, and plays outside of school.

Activity #2: Ask students to identify Jimmy’s main supporters and the nature of their support. Then ask them: Who are the supporters in your life? How do they show you support? How do you thank them for supporting you?

Face Challenges

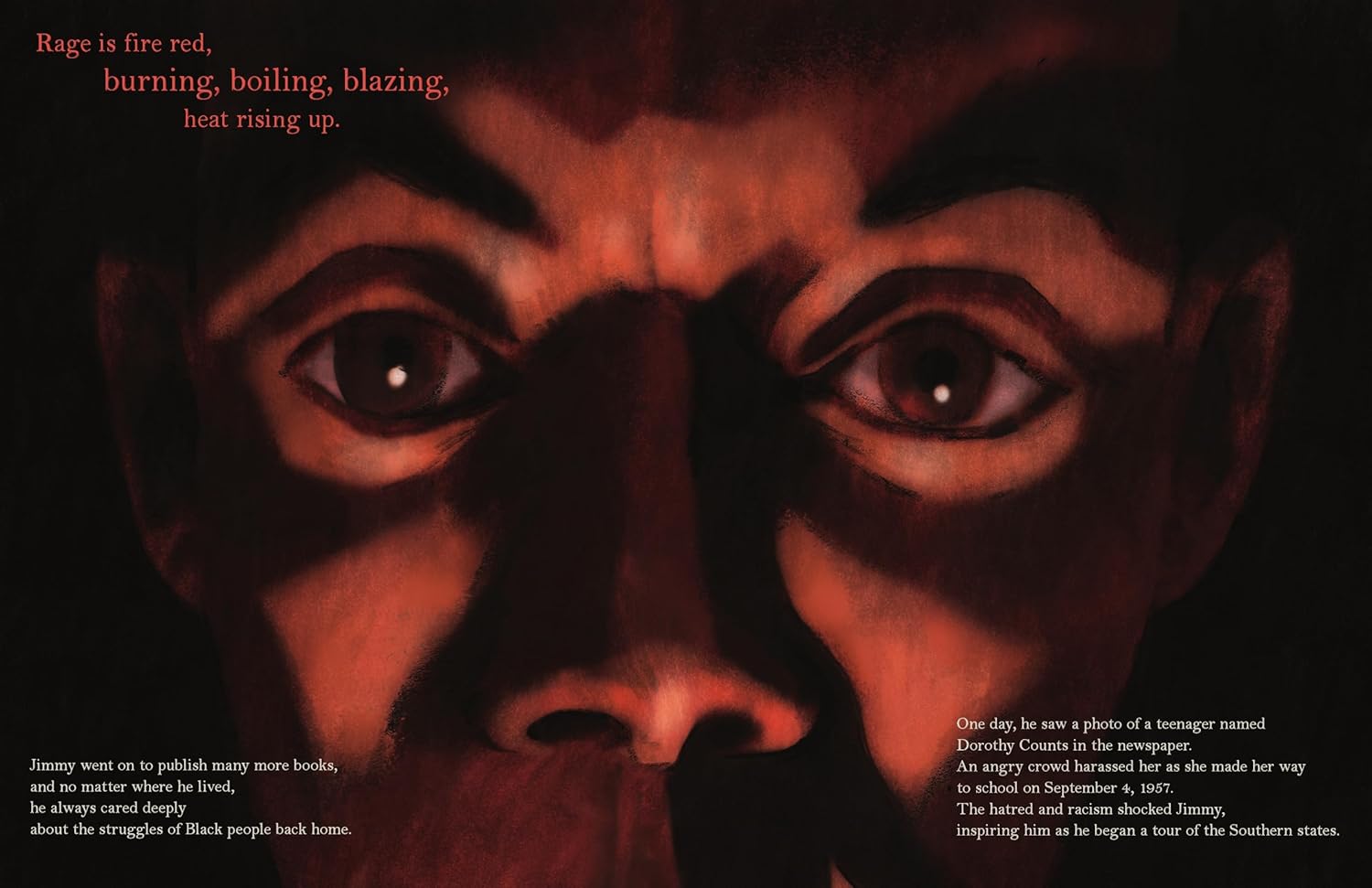

While Jimmy found joy in the rhythm of music, family, and books, he also found the blues, as a Black man dealing with discrimination and oppression in America. After he moved to Europe and no matter where he lived, he always cared deeply about the struggles of Black people back home. He took action by taking a tour of the Southern states in the U.S. He marched, protested, and wrote and spoke eloquently about the fight for freedom. Jimmy energized people of all ages and races to open their minds to new ways of thinking.

Activity #3: After inviting students to identify Jimmy’s challenges, ask students: What challenges have you experienced in your life? What actions did you or will you take to face those challenges?

Express Yourself

When Jimmy discovered the written word, he discovered true power. Writing gave him a voice and a channel to express himself. Jimmy also appreciated many types of artistic expression. He loved to sing and dance; music was an important part of his life. He was also interested in the colors of clothing, nature, and paintings. Hence the choice to tell his life story through the lens of a variety of colors. For example, one excerpt:

Writing is electric blue,

bright, brilliant swirls

of letters and words

flying, flipping,

flowing to the beat.

Activity #4: Explain to students that there are so many ways they can express themselves. Invite them to brainstorm: What are your favorite ways to express yourself? What colors do you connect with your different feelings and moods?

Writing Jimmy’s Rhythm & Blues: The Extraordinary Life of James Baldwin was one of the most exciting projects of my life. From the publication of his groundbreaking collection of essays The Fire Next Time to his passionate demonstrations during the civil rights movement, Jimmy used his voice fearlessly. My hope: One day every student will know the name James Baldwin – one of America’s greatest writers and intellectuals.

Published January 30th, 2024 by HarperCollins

About the Book: Celebrate James Baldwin’s one-hundredth birthday anniversary with the first-ever illustrated biography of this legendary writer, orator, activist, and intellectual.

Before he became a writer, James “Jimmy” Baldwin was a young boy from Harlem, New York, who loved stories. He found joy in the rhythm of music, family, and books.

But Jimmy also found the blues, as a Black man living in America.

When he discovered the written word, he discovered true power. Writing gave him a voice. And that voice opened the world to Jimmy. From the publication of the groundbreaking collection of essays The Fire Next Time to his passionate demonstrations during the civil rights movement, Jimmy used his voice fearlessly.

Michelle Meadows, author of Brave Ballerina and Flying High, introduces young readers to the great American novelist, essayist, poet, playwright, orator, and artist James Baldwin, who, with the fire of his pen, dared a nation to dream of a more equitable world filled with love. Brought to life with warm illustrations by Jamiel Law, Jimmy’s Rhythm & Blues chronicles the life of an incredible visionary who left an indelible mark on American literature and history.

About the Author: Michelle Meadows is the author of many acclaimed books for children. She loves dreaming up new projects and telling stories with heart. Some of her books include Flying High: The Story of Gymnastics Champion Simone Biles and Brave Ballerina: The Story of Janet Collins. Michelle also contributed to Black Ballerinas: My Journey to Our Legacy by Misty Copeland. With a passion for storytelling, Michelle graduated from Syracuse University with a dual degree in journalism and literature. Michelle grew up in Washington, DC, and now lives near the beach in Delaware with her husband. Visit Michelle at michellemeadows.com.

Thank you, Michelle, for this deep dive into Jimmy’s Rhythm & Blues and James Baldwin’s life!