“Scared Safe: How Horror Literature Can Comfort Young Readers”

When people learn what kind of young adult novels I write, I often get the comment, “Oh, I can’t read horror. I’m too scared!” I always respond with, “Oh, me too! I’m so afraid, I’m medicated!” I usually get a confused look in reply, “But . . .you write horror?”

I know, it doesn’t make a lot of sense at first glance, but I’ve always loved scary stories, even when I was quite young. My three older brothers usually had Creature Features on, a weekly television broadcast of cult horror movies, and my mother was always reading some gothic horror novel or another, so I was right there asking them all my questions, peeking at the screen from between my fingers. Yes, these things gave me nightmares, but no, that didn’t stop me. After many years of being a horror fan, I began my writing career with a young adult novel about the Latine boogeyman entitled Five Midnights. From that point on, I was hooked. After writing in this genre for over ten years and meeting a lot of other writers and readers, I’ve come to realize that a lot of us are like this: these stories scare us too, but we also find comfort from reading, watching, or listening to tales of the macabre. I have a theory why, at least in my own case.

Like many childhoods of that time, mine had its traumas. I was the fifth of five children, with sixteen years between me and my eldest sibling, and for five of my first eight years my father was dying of ALS. As you can imagine with all that was going on for my fairly large family, I often went unnoticed, quietly sitting in the background as my brother George watched Invasion of the Body Snatchers, or listening in on conversations about my father’s disease that were not appropriate for my young years. After my father passed, with only two of us kids left at home, my mother turned to alcohol for comfort. Me? I started buying horror comics, reading about dolls that came alive at night and killed their owners, corpses that rose from the grave to exact revenge. I was drawn to these dark tales because they made my difficult life seem bearable, particularly those that featured kids who, like me, had no autonomy, no voice, but when faced with the most unimaginable horrors they managed to triumph in the end. Weird as it was, those stories made me believe that there was hope, because though my young life sucked, at least there weren’t zombies breaking down the front door of our home. I am clearly not alone in this response; in fact, I came to find that it is supported by studies as well.

In his paper entitled, “Scaring away anxiety: Therapeutic avenues for horror fiction to enhance treatment for anxiety symptoms,” behavioral scientist Coltan Scrivner, PhD states, “Horror media may provide a unique avenue for individuals to manage anxiety by offering controlled exposure to fear, opportunities for cognitive engagement, and experiences of mastery over negative emotions.” He goes on to talk about the benefits of “scary play” for juveniles, “Much of human play takes place in the cognitive playground of a fictional world. Through fictional play, people can learn what a particular situation looks like and imagine how they would react and deal with it. As with more physical types of play, cognitive play with fiction can also serve as a rehearsal for negative emotions and how to manage them.” So, horror stories give young readers an opportunity to practice their responses to trauma in a safe and fictional environment.

During a recent interview I was asked how writing horror for teens differs from writing horror for adults. My answer is always the same: hope. When you’re writing for young people, you’re writing for a vulnerable population. You have responsibility toward your readers. With adults, you don’t have to consider audience at all, you just write. And in the case of adult horror, it can be as dark, violent, or disturbing as you’d like. But with young people, I feel that even the darkest stories should end with a certain amount of hope, and, perhaps, agency for the young protagonists. But along the way, the road can be pretty dark: today’s youth can take it.

In any young adult novel, it is partially our job as writers to throw as many roadblocks at our main characters as possible, sometimes in the form of trauma or truly horrific things, because, put simply: conflict makes for a more interesting story. The more conflict, the better. No one wants to read about someone’s perfect life, because I don’t believe anyone actually has one. It would seem empty. I often think about the first time I read the Lord of the Rings. I couldn’t stand the fact that Frodo and Sam continued to encounter unspeakable evil for thousands of pages, and I gnashed my teeth for hours at a time. I was like, “Just let them throw the damn ring into the fire already!” But it kept me turning pages. No one wants to read a version where they’re magically flown to Mount Doom, Frodo doesn’t have an internal battle with evil but rather just tossed it into the lava, middle earth is saved in the first fifteen minutes, and there was much rejoicing. Rather, it is the act of overcoming that elevates a tale to one that we love and reread over and over. And it is these kinds of stories that almost always end with hope.

So, whether or not you are someone who enjoys horror, you will probably encounter a student or other young person who expresses interest in books of the scary persuasion. What I’d like to ask of you, is this: don’t assume about the child is drawn to these kinds of stories because they are receding into darkness, but rather consider that they might be trying to claw their way out of it, and books of this kind help them do just that. Because in the darkness of horror, young readers often find the light they need to face the real world.

I certainly did. And I turned out alright. (Well, more or less. 😉

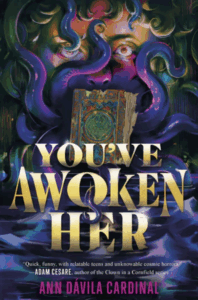

Published June 17th, 2025 by HarperCollins

About the Book: Fans of You’re Not Supposed to Die Tonight and Your Lonely Nights Are Over will love this thrilling YA horror about a string of disappearances and “accidental” drownings in the Hamptons, the changing relationship between two best friends, and their desperate attempt to not be the next victims of a Lovecraftian monster terrorizing the coastline.

Gabi should be thrilled to be visiting his best friend for the summer. But with its mansions, country clubs, and Ruth’s terrible new boyfriend, Frost Thurston, the Hamptons is the last place he wants to be. And then Gabi witnesses a woman being dragged under the ocean by what looks like a tentacle . . .

When no one—not the police or anyone else—seems to care, Gabi starts to wonder if maybe the beachside town’s bad vibes are more real than he thought. As the number of “accidental” deaths begins to climb, the Thurston family name keeps rising to the top. And what’s worse is that all the signs point to something lurking beneath the water—something with a hunger for blood.

Can Gabi figure out how the two are intertwined and put an end to the string of deaths . . . before becoming the water’s next victim?

About the Author: Ann Dávila Cardinal is a writer and part-time bookseller with an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her young adult horror novels include You’ve Awoken Her, Breakup from Hell, and Five Midnights and its sequel, Category Five. Ann lives with her husband in a little house with a creepy basement and is always on the lookout for parts of monstrous creatures floating in the Vermont rivers as Lovecraft wrote about. Visit her online at anndavilacardinal.com.

Thank you, Ann, for sharing the research behind the need for horror!