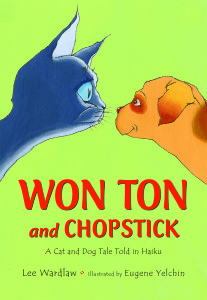

“Eight Things I Learned from My Cats about Writing Haiku”

by Lee Wardlaw

1. There is no yesterday; there is no tomorrow. There is only you, scratching me under my chin right now.

Haiku poems focus on a right-this-instant experience—or from a memory of that experience. So remind your students to write in the present tense.

2. When poised at a hole, remain still—and use your ears, eyes, nose, whiskers and mouth to detect a lurking gopher.

Observation is crucial to haiku. It’s hard for children today to quiet their minds, especially when they’re constantly bombarded with TV, internet, iPhones, video games, etc. So take them outside, away from all of that! Encourage them to sit alone on the playground, under a tree, on a sunny bench, whatever, and use all five senses to absorb, appreciate, and anchor the moment.

3. Be patient. Then, when least expected—pounce!

Haiku captures ONE moment in time, revealing a surprise . . . or evoking a response of a-ha! or ahhh. This pounce helps the reader awaken and experience an ordinary moment or thing in an extraordinary way.

4. Most cats have 18 toes—unless we’re polydactyl; then we might have 20, 22, even 28 toes!

Japanese haiku feature a total of seventeen beats or sound units: five in the first line, seven in the second, five again in the third. But this 5-7-5 form doesn’t apply to American haiku because of differences in English phonics, vocabulary, grammar, and syntax. Too many teachers focus only on the 5-7-5 because they use haiku as lesson about syllables. Please don’t! When children force an unnecessary adjective or adverb (or a bunch of adverbs) into a haiku simply to meet the 17-beats rule, it ruins the flow, brevity, meaning, and beauty of a poem. It’s not a poem at all, just a laundry list. You end up with poems like this:

My cat is so cute.

He’s really, really, really

cute and so fluffy.

Encourage your students to experiment with any pattern they prefer (e.g. 2-3-2, 5-6-4, 4-7-3)—provided the structure remains three short lines. Remember: what’s most important here is not syllables but the essence of a chosen moment.

5. When I’m out, I want in; when I’m in, I want out. Mostly, I want out. That’s where the rats, gophers, lizards, snakes, bugs and birds are.

Traditional haiku focus on themes of nature, and always include a kigo or “season” word. This doesn’t mean you must be explicit about the weather or time of year. A sensorial hint (e.g. a green leaf indicates spring; a russet leaf indicates fall) is all that’s needed.

6. What part of meow don’t you understand?

Tease a cat and it won’t bother to holler—it will bite and scratch. It shows its annoyance rather than tells. Good haiku follows suit. Instead of explaining, haiku should paint a picture in the reader’s mind of the feeling it evokes. So encourage children to show the reader how cute and fluffy their cat is instead of just telling us.

7. If you refuse to play with me, I will snooze on your keyboard, flick pens off your desk, and gleefully shed into your printer.

Yes, haiku has “rules,” but remember to play! Encourage students to use words like toys, to frolic with them in new ways to portray images, emotions, themes, conflicts and character.

8. When in doubt, nap.

Good writing comes from revising. But before working on a second (or third . . . or fourth!) draft, both the students and their haiku need a “nap.” Set aside the poems for a few days (a few weeks is even better!). What needs revising will be much more obvious if the poems are read again with rested eyes, alert ears, and a fresh mind.

About Lee Wadlaw:

Lee Wardlaw swears that her first spoken word was “kitty.” Since then, she’s shared her life with 30 cats (not all at the same time) and published 30 books for young readers, including Won Ton: A Cat Tale Told in Haiku, recipient of the Lee Bennett Hopkins Poetry Award and many other honors. Lee has a B.A. in Education, an AMI-Primary Diploma from the Montessori Institute of San Diego, and is finishing her M.Ed. in Education/Child Development. She lives in Santa Barbara with her family. http://www.leewardlaw.com

and