Sofia is a 13-year-old brilliant reader who aspires to be a book reviewer. Since she was 8 years old, on select weeks, Sofia shares her favorite books with other young people her age! She is one of the most well-read youth that we know, so she is highly qualified for this role!

Dear readers,

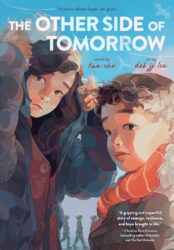

Let me introduce you to The Other Side of Tomorrow by Tina Cho, a heartfelt graphic novel about the dangers of escaping North Korea. The story follows two kids on their journey to leave the country for a better life. You come along with them each step of the way, witnessing the horrible things North Koreans have to go through just to get to freedom. This story is told in beautiful illustrations that capture the emotions of the reader as well. I loved looking through the eyes of someone escaping communism, in a search for a better life, and feel that it is eye opening to read this. The Other Side of Tomorrow was a really grounding book that really makes you grateful for all you have, while also sharing others’ important stories and experiences.

Goodreads Summary

Perfect for fans of Illegal and When Stars Are Scattered, this poignant and moving graphic novel in verse captures the dangers and hope that comes with fleeing North Korea and reaching for a brighter future through the lives of Yunho and Myunghee.

From never knowing where they’ll find their next meal to avoiding soldiers lurking at every corner, many North Koreans have learned that sticking around can be just as deadly as attempting to flee … almost.

Both shy, resourceful Yunho and fierce, vibrant Myunghee know this. So when they each resolve to run away from the bleak futures they face, it’s with the knowledge that they could be facing a fate worse than death. While Yunho hopes to reunite with his omma, who snuck across the border years ago, Myunghee is reaching for dreams that are bigger than anything the regime would allow her to have.

The two are strangers to each other until a chance encounter unwittingly intertwines their fates and Myunghee saves Yunho’s life. Kept together by their dreams for a brighter future, they face a road plagued by poisonous jungle snakes, corrupt soldiers, and the daily fear of discovery and imprisonment. But with every step toward freedom, there is also hope. Will it be enough for both of them to make it to safety without losing each other along the way?

My Thoughts

The Other Side of Tomorrow will certainly pull at your heartstrings, as it did for me. As you come along the journey of Myunghee and Yunho, you get to experience the hardships people fleeing from North Korea face. Before reading this book, I thought that once you escape North Korea, which is hard enough, you are free and can build a new life. What I discovered through this book is that my previous statement could not be further from the truth. Even if you make it to China, they have an extradition treaty with North Korea, meaning that if anybody realizes you are from there, you will immediately get punished and sent back. Additionally, Chinese soldiers receive monetary compensation for every North Korean they report, (incentivizing)meaning they will always be on the lookout for them. Even though this book is sad, I think it is important to know what people on the other side of the world are going through, so we can spread awareness and help them. The beautiful illustrations enhance the reading experience, wonderfully telling this story of pain and hardship. I hope you enjoy this wonderful book!

I would recommend this book for ages 11+ because of the complex topics it discusses which may be hard to understand for younger readers. The simple way in which The Other Side of Tomorrow is written makes it easier to understand for all readers. The only thing I would say is that this is an incredibly sad book, about the many hardships escapees from North Korea have to face.

**Thanks so much, Sofia!**